The tide is going out in AI

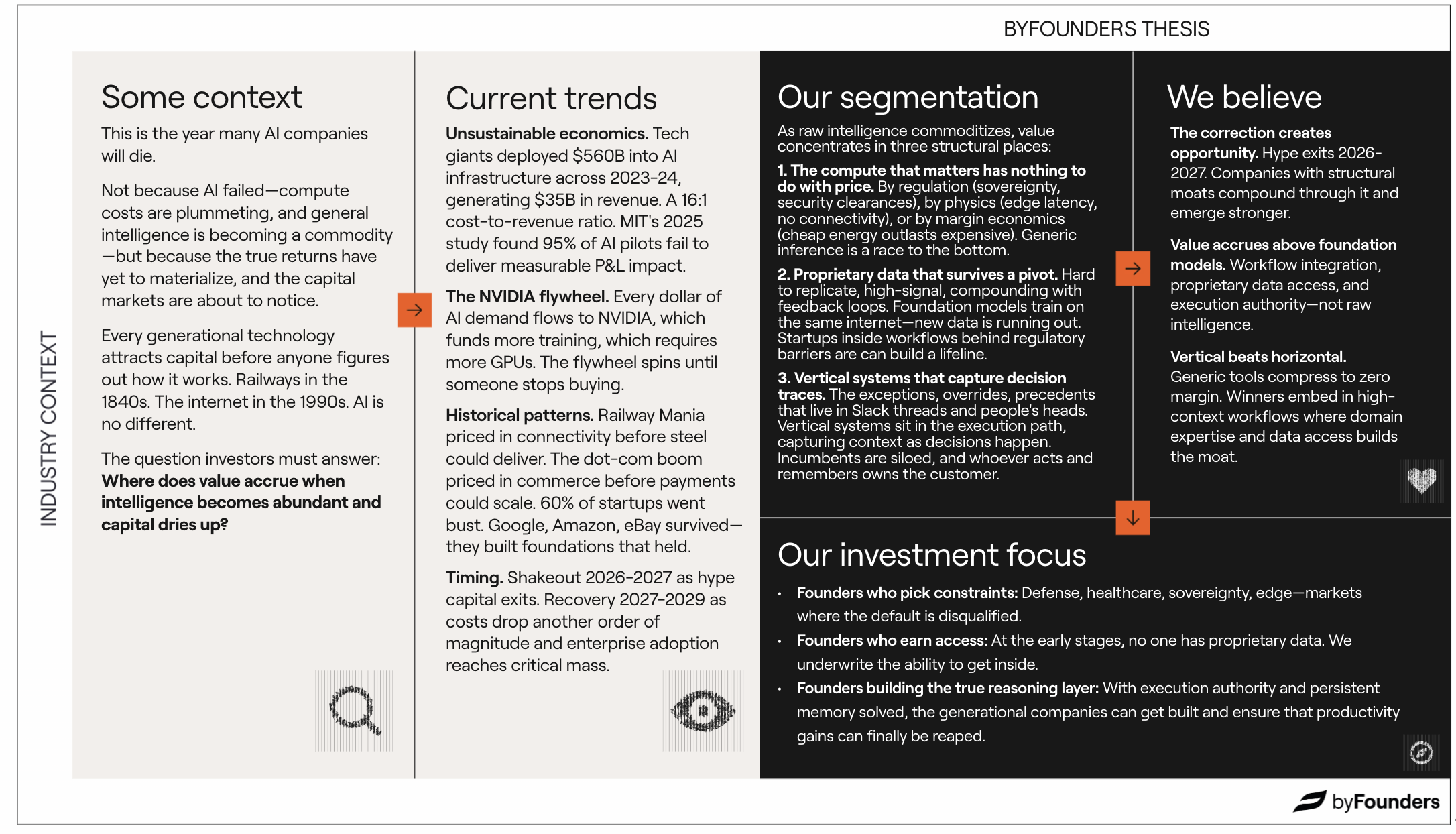

As intelligence becomes cheap and capital becomes scarce, only companies with real structural moats will survive the coming AI reckoning.

Some of you might have spent the holidays reading through everyone’s 2026 AI predictions.

There were lots of them. More agents. Better reasoning. The year of agents will finally be here. A different prediction is that this is the year many AI companies will die.

It seems every generational technology arrives with the same cosmic joke: the market figures out it matters before anyone figures out how it works – railways in the 1840s, electricity in the 1890s, the internet in the 1990s.

AI has been no different. Every founder these days is building the next generational AI company, and for two years, capital has flooded in at historic rates. At the same time, the answer to "will AI transform everything?" is obvious but useless: of course it will. But while technology races toward AGI and inference costs plummet, the returns haven't materialized, and capital markets are about to notice.

The tide is receding in AI, and to avoid being left with the naked swimmers, investors must ask themselves one simple but pivotal question before writing a check: Where does value accrue when intelligence becomes abundant, and capital dries up?

As raw intelligence commoditizes, we believe value concentrates in three structural places:

- Compute that is constrained by energy access, sovereignty, and domain

- Access to data in highly regulated environment that is truly proprietary and truly difficult to gain access to

- Vertical systems that are deeply embedded in workflows, and understand all the weird pieces of the puzzles you’d usually keep locked somewhere in the back of your brain

The tide is receding

You don’t need to crawl the internet for long to see the signals. This could very well be the millionth piece quoting MIT's infamous 2025 study, which found 95% of AI pilots fail to deliver measurable P&L impact.

$560 billion was invested in AI infrastructure across 2023-24, while only generating $35 billion in revenue - that’s a 16:1 ratio (!) that would sink most normal businesses. Simultaneously, the public market multiples are far below the private valuations, making exits unattractive.

And take good old Microsoft. Since 2020, it has invested multiple hundreds of billions of dollars into AI infrastructure and OpenAI. Its premier product from this colossal investment is Copilot (or, Clippy on steroids), but yet, it turns out people seem to stop buying it.

Stanford HAI's James Landay predicts 2026 will bring the reckoning - more companies will say AI hasn’t shown productivity increases, and more AI projects will fail. A movie we’ve watched before.

- In the 1840s, Railway Mania priced in nationwide connectivity before steel production could deliver. The survivors built operational infrastructure connecting central hubs.

- In 1999, the dot-com boom priced in digital commerce before bandwidth and payments could support profitable scale. 60% of startups went bust. The survivors—Google, Amazon, eBay—had built foundations that held.

Yes, the technology continues to improve—a 280-fold cost reduction in just two years—but capital markets (eventually) don’t really care about exponential curves; they care about returns.

The tide will hit a low point in 2026-2027 as interest rates on capital increase. Recovery comes in 2027-2029 as costs drop another order of magnitude and enterprise adoption reaches critical mass. So, who gets to keep their swimsuits on?

Compute with the right constraints

In October, Google announced it's processing 1.3 quadrillion tokens per month—roughly 160,000 tokens for every person on Earth, or more than a Lord of the Rings-length book per person, every month.

Hyperscalers are locked in a high-stakes game of chicken: each massive spend forces rivals to commit even more, prioritizing the risk of being left behind over future overcapacity. This means general-purpose optimization is commoditizing fast. Quantization, speculative decoding, and hardware-aware compilation are techniques that are well understood and rapidly standardizing.

Building a competing business on generic compute optimization is like building on sand. AI inference startups prove the point. Developer experience, price, and performance have all converged across platforms—the optimization techniques are known, and what's left is a brutal race to the bottom, where most can't absorb their costs long-term. Foundation model providers, data platforms like Databricks and Snowflake, and backend players like Vercel are all squeezing from different directions.

.png)

This changes the game: the remaining durable compute moats exist only where infrastructure cannot be easily swapped out. In practice, that means:

- Energy is the ultimate margin play. Electricity runs about ~20-30% of data center costs. Small differences in power pricing create massive cost divergence at scale. If (or when) AI demand cools and excess capacity floods the market, operators with expensive power can't cut prices enough to survive. Those with cheap, reliable energy—hydro, nuclear, stranded gas—can drop prices while staying profitable, absorbing market demand. And unlike fiber optic cable or GPU clusters, power infrastructure takes years to build. Nuclear plants take 10-15 years to build, and major transmission lines face decades of regulatory approval. Verda exemplifies this: operations in Finland and Iceland give access to clean, low-cost electricity—an advantage when energy-hungry AI workloads strain data centers.

- Domain-embedded compute creates genuine lock-in. In healthcare, defense, and industrial systems, you can't swap in a different GPU cluster, and models must run inside tightly coupled environments with strict latency, compliance, and physical constraints. And autonomous vehicles can't wait for cloud round-trips, just like surgical robots need sub-10ms inference. Whether the constraint is regulatory or physical, the result is the same: generic cloud compute isn't an option, and replacing what's there means re-certifying, re-integrating, and accepting operational risk.

- Sovereignty is permanent market segmentation. Data residency laws dictate where AI can run. Even if hyperscalers offer better prices, they may not be permitted to serve government, defense, or critical infrastructure workloads. A defense startup with security clearances has a captive customer base, just like a European AI company serving banks has no hyperscaler alternative.

Anduril sits at the intersection—defense clearances, edge inference in GPS-denied environments, and purpose-built silicon. At $14B valuation and $1B in 2024 revenue, they've proven what happens when a startup picks the right constraints.

.png)

Proprietary data survives pivots

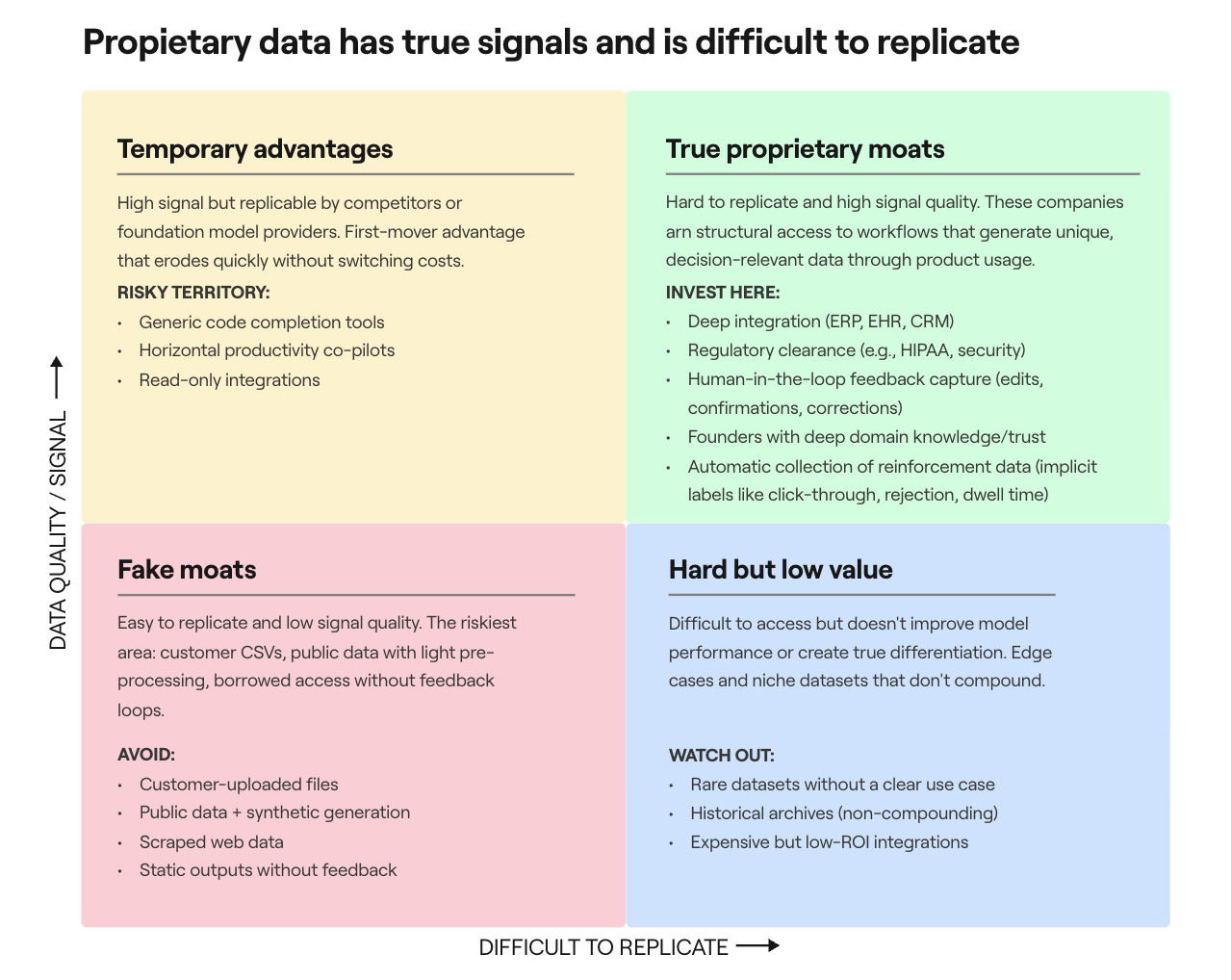

Every foundation model trains on the same internet. New high-quality data is becoming scarce. Stanford HAI notes models are "asymptoting"—hitting limits because we're running out of training data, and what remains is increasingly low quality.

The scarcest resource in AI is access to workflows that generate labeled, decision-relevant data that actually improves model performance.

True proprietary data has three properties: it's hard to replicate (legally restricted, relationship-dependent), high-signal (generated through real usage), and compounding (continuously improving the model through feedback loops).

Consider what this looks like in practice. Corti sits inside live clinical conversations, capturing diagnostic reasoning behind barriers no competitor can easily cross. Legora works alongside lawyers on real cases, learning from expert corrections and outcomes. Synthesia captures creative workflows with human feedback—edits, preferences, and style corrections that accumulate over time.

Now consider what doesn't count. Customer-uploaded CSVs they could take to a competitor. Public datasets with light preprocessing. Read-only API access without feedback loops.

To assess whether access is difficult to replicate: Does the product sit where sensitive data is created? Does it require deep integration and regulatory clearance? Do founders have domain credibility? Does the workflow break if the product disappears?

To assess whether the data has signal: Does every interaction make the product smarter? Does it capture human-in-the-loop feedback—edits, confirmations, corrections? Does it see outcomes, not just inputs?

Getting "inside" the customer is brutally difficult, and incumbents are too slow to rewire workflows. Foundation model providers are too general to care about micro-context. Startups in the middle layer—close enough to capture unique signals, specialized enough to learn from them—are the only ones who can gather intelligence over time (if, of course, they earn the right to do it). Even if the initial product-market fit doesn't hit, the value of the data alone offers a lifeline.

Vertical integration reaps the true productivity gains

As foundation models commoditize, two things become genuinely scarce: execution authority—the right to trigger real actions in high-stakes workflows—and persistent memory—the ability to accumulate context over time rather than resetting with each prompt.

But "persistent memory" requires precision. ****Decision traces—the exceptions, overrides, precedents, and context that currently live in Slack threads, deal desk conversations, escalation calls, and… well, people's heads.

Let’s take a few examples:

- Exception logic. "We always give healthcare companies an extra 10% because their procurement cycles are brutal." Nope, not logged in your CRM.

- Precedent from past decisions. "We structured a similar deal for Company X last quarter—we should be consistent." No system links those deals or records why.

- Cross-system synthesis. The support lead checks ARR in Salesforce, sees escalations in Zendesk, reads a Slack thread flagging churn risk, and decides to escalate. That synthesis happens in their head, while the ticket just says "escalated to Tier 3."

.png)

The core problem is that reasoning—the thread connecting data to action—has never itself been treated as data. Solving this requires two things: 1) systems must be deeply embedded in the actual flow of work, and 2) the relationships they capture need to be represented in a computationally efficient way.

What this really means is building something like an enterprise context graph.

First, you need observability across fragmented tools. Real understanding comes from capturing activity wherever work actually happens—a document edited in Google Docs, a message sent in Slack, a meeting scheduled, a record updated in Salesforce. Each of these needs to be captured directly through its connector.

Second, you need activity data: discrete, timestamped actions like document edits, field updates, comments, and messages - captured in chronological order and a clear understanding of the state changes.

Only then can you infer higher-level constructs. A sequence of document creation, edits, Slack messages, and record updates might collectively represent a customer onboarding effort—even if no single system ever labeled it as such.

This is technically demanding, and unlike consumer applications, these graphs can't be built at internet scale, and data can't be pooled across customers. The resulting datasets are smaller and off-limits to human review for privacy reasons, which means the graphs have to be inferred algorithmically, one customer at a time.

Our investment focus

2026 will be the year of reckoning. Like most other predictions, it will probably be wrong, and there will be plenty of successful companies left that win because they got in at the right time, obsess over product, and have their distribution nailed from the start.

We first and foremost back incredible founders and ambitious teams. But, as the tide goes out, capital markets dry out, and general intelligence races towards commodity, it gets increasingly more difficult to survive without clear structural advantages. These are the companies we’ll be keeping an eye out for.

.jpg)